As my Doctoral research at the University of Hertfordshire progresses, it is becoming clearer that the topic of difficult conversations at work is multifaceted and complex.

In my last blog I spoke of my personal interest in the phenomenon as well as my professional interest it is important for me to use an evidence-based practice (EBP) approach to seeking answers to the questions I have about the nature of difficult conversations at work. Having a personal connection with the topic is valuable, as it offers me a unique lens through which to view the findings of my research, but it also highlights the importance of taking a pragmatic approach to my research to ensure I am using all available methodologies and approaches to explore this phenomenon and that any advice or recommendations I may make as a result of my research are based on, concerned with, or verified by observation, experiences, gathered data, and psychological theory, rather than being based purely on personal intuition, personal experience, personal beliefs or pure logic.

So, with that in mind, I was conscious that my research is highly driven by my personal experiences of having difficult conversations at work about my health and the challenges I have faced. For me, conversations of a personal nature are the most difficult to have. I don’t struggle with feedback conversations or performance management discussions. I don’t find them awkward or challenging. Instead, I see them as supportive and collaborative conversations, an opportunity for learning, development, and growth. They don’t fill me with dread, and I don’t shy away from them whether I am the one giving or receiving feedback, or we are discussing mine or another person’s performance. But when I need to talk to people about my health, something switches and I experience a full spectrum of thoughts and emotions that can be overwhelming, often resulting in me wanting to build a big wall of protection around myself and avoid avoid avoid! and I find myself asking, why is that?

It also made me curious about how other people experience difficult conversations at work and whether like me, there are some types of conversations that people find more difficult than others and if so, why might that be?

My second PhD study explored perceptions of conversational difficulty to see if I could identify whether there were certain types of conversations that were perceived to be more difficult than others.

I created a questionnaire that explored a range of scenarios in which a difficult conversation may occur, and participants were asked to self-rate how difficult they would find a conversation of that nature, (there was the option for people to provide an explanation for the ratings they gave).

Unsurprisingly, who you have a difficult conversation with matters. In my interview study (discussed in part.1 what is it really like to have a difficult conversation at work), individuals interviewed commented on how the approach and reactions of a conversation partner greatly influence the overall experience and potential outcomes of a difficult conversation. They also talked about how the power dynamics within a relationship can influence how confident they felt at challenging their conversational partner.

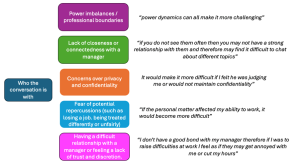

These views were supported in my second study with participants rating conversations with a manager as more difficult than conversations with a peer or co-worker. They provided a range of examples as to why they felt this way (See image below)

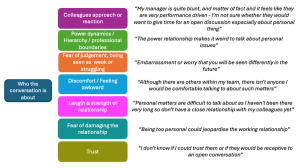

The next important observation from this second study was that individuals rated personal conversations as more difficult than work-related conversations. There were a number of reasons given for these ratings (see image below) however, this appears to be closely related to who the conversation is with, as the strength and length of the relationship, and trust within a relationship played an important role.

The final salient observation from this second study was that individuals rated conversations about themselves as significantly more difficult than conversations about another person. It suggests that we find it more difficult to discuss our own challenges, difficulties, or problems than other peoples. Reasons for this stem from our willingness to be vulnerable at work and concerns about exposing our emotions amongst other things (See image below for more).

What stood out for me was the inter-relationship between these three elements of who the conversation is with, the type of conversation it is and who it is about. At the beginning of my research, I was curious about whether there was a way to make difficult conversations less difficult, but it is becoming obvious that there is no one thing that determines if a conversation will be difficult and how each of us experiences a conversation is dependent on any number of factors.

I see difficult conversations at work as sitting on a continuum from hard to hardest, or difficult to most difficult. The absence or presence of certain factors influence where on that continuum a specific difficult conversation will be and what our experience of it will be.

Influencing factors may include:

- The workplace culture and environment

- The relationships we have at work

- Our own skills, traits and attributes

It may not be possible to make difficult conversations less difficult, but we can take steps to help individuals feel confident and ready to approach them. Some may view this as making them easier, but I think there are subtle differences.

There are lots of recommendations on how to approach or navigate difficult conversations in the workplace, often these involve frameworks or models with practical steps to follow when having a difficult conversation. It is of course useful to have guidelines or processes we can follow to help us plan our approach, and keep in mind what we need to be aware of throughout. However, I question how effective these models or frameworks are without the foundations of organisational culture and environment, relationships at work and individual skills, traits and attributes being in place, especially when it comes to those emotive and sensitive personal conversations that are extremely significant and meaningful to us as individuals.

My own experiences of difficult conversations may or may not have been improved if I had used a framework or model to inform my approach or to help me prepare, however I am confident that the culture and values of Zest Psychology, (as outlined in my previous blog), and the relationships I have with those I work with have made a difference to my experiences of these conversations in a positive way.

The conversations are still difficult, due to the topic and the sensitive nature of what we are discussing, but I can navigate them because I am supported through them, I feel safe to speak freely and openly as we embed this into our ways of working, and I can be vulnerable without fear of judgement.

There are still a lot of unanswered questions in my research, and I’m excited to continue my research journey. My next study will explore ‘readiness; to have a difficult conversation at work and I will be delving into the relationships and influences of concepts such as psychological safety, sense of belonging and connectedness, emotional intelligence (EQ) and psychological capital to understand if and how any of these factors influence our experiences of difficult conversations at work.

If you would like to know more about this research or are interested in taking part in any future studies, please get in touch rachel@zestpsychology.ccom / rs20ada@herts.ac.uk

One of the things I like most about concurrently working at Zest and being a researcher at Uni of Herts, is that my research can be put to immediate use! For example, we support leaders and HR business partners in their work by providing evidence-based leadership coaching and designing team and organisational development solutions.

If my blogs have resonated, then get in touch to see how Zest can help you. Visit www.zestpsychology.com to find out more.

Author: Rachel Smith (GMBPsS)

Psychologist at Zest Psychology / PhD student at the University of Hertfordshire

(MSc Occupational Psychology, BSc (Hons) Psychology)